There is a progressive shift in the models and methods used for business valuation. This is part two of the IBCA’s series on business valuation methods. We take a rundown of alternative valuation methods, which are finding their application in the knowledge economy.

The holy grail of valuation is determining the potential of an investment opportunity. It involves satisfying both the seller and the investor, and in the case of unlisted private companies, it is hardly ever a walk in the park. Celebrated value investors like Warren Buffet and Benjamin Graham prefer historical data over forecasts to evaluate an investment opportunity. They say projections are fallible and thus illusions. The problem with historical data, though is it lags when the earnings of a company change rapidly. In practice, every investment decision is futuristic and based on projections, and historical data is used to make those forecasts. The question for valuation professionals is not of whether or not to make projections or use historical data – but which set of approaches and tools to use to do so.

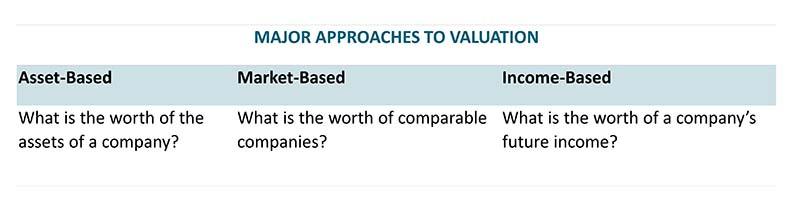

To assess the value of a business objectively, professionals need the right models that can provide a sound way of capturing the twin influences of risk and return. Two of the most common methods – DCF and multiples – used for business valuation were discussed in the first article where three main valuation approaches were explained (a quick glimpse in the table).

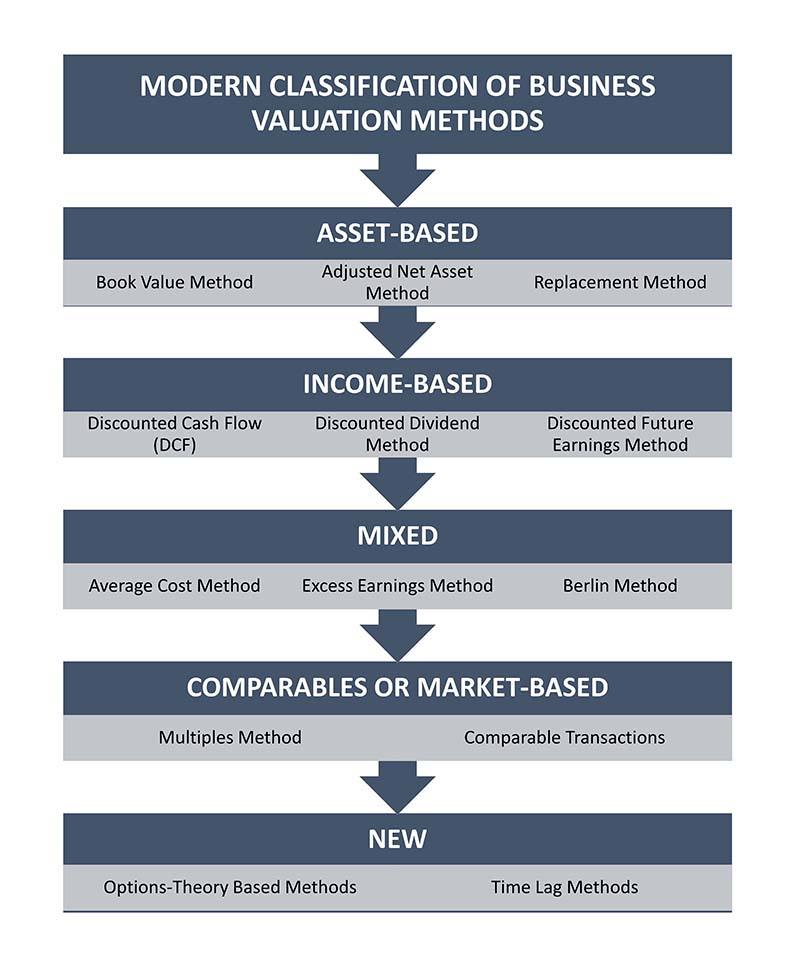

In the second part, we take a look at modern-day classification of business valuation approaches, and a few alternative (and more intuitive) methods to valuation, which offer a nuanced understanding of an investment. Taking in account alternate methods is necessitated by the mounting importance of intellectual capital, technological transformation, and intangible factors in new-age businesses. A summary of some of the key valuation methods (within the green boxes) other than DCF and multiples.

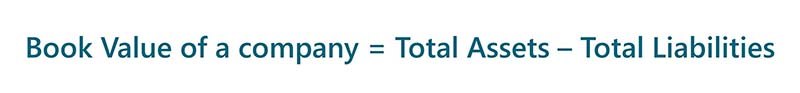

It calculates the total value of the assets of a business as found on the balance sheet. Book value represents the entire amount a company is worth if at a given point its assets are sold and liabilities are paid. It is also known as the balance sheet or Net Asset Value (NAV) method to value a business.

This method determines the minimum price a seller would be willing to accept. Thus, in many ways, it establishes the floor value of a business.

Financial statement analysis is used to measure the net value of a business’s assets. It includes all original purchasing costs of its assets (adjusted for depreciation, amortization, among others).

When to use:

If a business has low profits, but valuable assets.

If the value of a business can be fairly represented by its underlying assets.

If the value of intangibles such as goodwill is not too significant (such as when a business is recently set up).

When NOT to use:

If the financial statements don’t accurately reflect the value of the assets, by the virtue of possible losses not reflected on the balance sheet or other reasons.

If the intangibles like goodwill, brand value, marketing infra, talent, among others, constitute a majority portion of a company’s value. Consider a technology or a fashion designing firm. They may have little book value but are worth mainly on human capital.

If changes in the industry or economic environment have made the assets redundant to the present, and lose their ability to create net positive cash flow.

Limitation: Book value method relies on historical costs spent or earned by the business. Since it doesn’t consider the earnings potential of assets in the future, alone it cannot make a very reliable metric for valuing a going concern.

It is the most commonly used asset-based approach. Under the adjusted net asset method, the valuation is done similarly to book value, but the values of a business’s assets and liabilities are adjusted to reflect their current fair market values (FMV). The result is, it makes this approach appropriate for both going concern or liquidation.

The method takes into account both the tangible and intangible assets, along with off-balance sheets assets and non-recorded liabilities, say leases. Adjusted Net Asset Method reveals the market viability of a company and if the company has been earning fair returns on investments for the owners.

When to use:

If valuing a holding company, or a capital-intensive business.

If a business has been continually generating losses.

If income-based and other valuation methods indicate a value lower than the adjusted net asset value.

When NOT to use:

If a business is heavy on intangibles. Even though the method accounts for them, it doesn’t effectively distinguish tangibles and intangibles. For instance, the value of strong customer relationships, intellectual property assets, etc.

If the fair return on assets cannot be determined accurately.

If you intend to find out the opportunities for maximizing business value for going concern as the cause of excess earnings is difficult to determine by this method.

Limitation: Many analysts call this method deceptively simple. Figuring out the FMV is one of the major limitations that make this method more complex than it may seem at the onset.

This method values a business by estimating the cost of replacing its tangible assets. It is effective when the aim is to measure the total financial outlay that would be required to restore all assets of the valued company in full-shape.

It can be calculated by deducting Physical and Moral Wear (technical wear indicator, technology change, depreciation, etc.) of an asset from Gross Replacement Value (of a new fixed asset).

When to use:

If deciding on whether it would be profitable to buy a business, or build it from scratch.

When NOT to use:

If the company is liquidating or declaring bankruptcy.

Limitation:Process related costs involved in continuing the company, and the value of intangibles are not efficiently dealt with under this method.

A derivative of the forecast cash flow (DCF) approach, the Discounted Dividend Method (DDM) determines the intrinsic value of a company. It is calculated as the sum of discounted expected future cash flows.

Where,

r = cost of equity capital

g = estimated future dividend growth rate

When to use:

If a company has long and consistent records of paying stable dividends.

If making an investment primarily based on expected dividends.

When NOT to use:

If valuing a business operating in an unpredictable environment riled with significant risks.

Limitations: Dividends are discretionary, and this makes the projections of DDM tricky. The valuers are not only supposed to predict how a company will perform but also how it will make decisions for the distribution of dividends versus reinvesting profits.

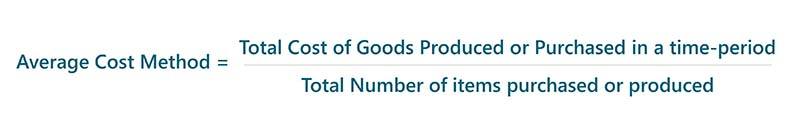

Inventories are largest of the current assets of a business. This method is among the three most commonly used inventory valuation methods. It uses the weighted-average of all inventory produced or purchased in a given period to assign the cost of goods sold or available for sale.

When to use:

If the inventory items are significant and distinguishable (like properties or construction material).

Limitation: When the cost of inventory varies by significant margins, valuing it doesn’t give an apt measurement of the cost of inventory. Your estimated pricing may not recover the costs.

A very old method, excess earning is controversial but has not lost its usage. From valuing the worth of a person in divorce cases to valuing intangible assets of a business, it continues to serve its purpose.

The method was developed by the US treasury. It wasn’t initially intended as a business valuation tool, but due to its simplicity, it has made its place in the domain. To value a company, it:

Estimates the market value of net tangible assets;

The value is then multiplied by a rate of return to calculate estimate earnings attributable to tangible assets;

The earning figure from the previous step is deducted from overall earnings to estimate the earnings attributable to intangible assets;

Finally, to calculate the value of the intangibles, the intangible earnings are divided by a capitalization rate (which estimates what the company is expected to produce in the future. Achieved by computing the present value of average annual net income).

When to use:

If a business involves significant intangible assets.

Limitation: The subjectivity is prominent in this method. For instance, when determining the rate of return to attribute to net tangible assets or capitalization rate for intangibles.

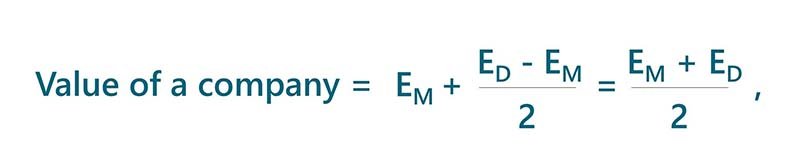

Many new methods (such as UEC, Stuttgart) of business valuation have emerged, which combine income-based and asset-based approaches. Berlin method is one such tool. It determines the value of a company by taking sum of its net asset values, along with half of excess value determined through income method above the asset value.

Where,

EM = value of equity estimated using asset-based method,

Ed = value of equity estimated using income-based method.

Traditionally used valuation methods prove insufficient to capture the value of (hypothetical) options crucial to many investor decisions. With advances in options-theory based methods, determining the value of an underlying business has become comparatively robust. One of these is a (real) options method. It accommodates the “what if” dimension in a valuation.

Real options analysis is a viable method to value a business or an investment opportunity, which includes if or else choices. It allows investors to estimate the opportunity cost of continuing a business or abandoning it.

When to use:

If valuing a business in trouble that has made large losses.

If valuing a startup or a new business, which is expected to lead value from ‘rights’ such as a patent or an innovative service.

If valuing a natural resource business.

If aiming to find out how a business will respond to the changing market conditions.

Limitation: The process of valuation through this method is complex and requires making many subjective choices and expert judgments. It includes designing high-charged decision trees and involving stakeholders’ preferences.

Evaluating a business is more than an estimation problem: it is a conceptual issue. It involves judgment.

There are several different valuation methods you can use, and every method sheds light on some aspects of the truth. Choice of the tool is impacted not only by the objective of valuation, but the type of the business, areas of activities, economic situation, and other determinants.

The job of a valuation expert, investment analyst, or a professional is to weigh the different methods, select the most appropriate ones, and triangulate a value that makes the most sense. A quick rule of thumb would be to not just arrive at one number but a range of values, and then deciding where within that range of values the actual value of a business lies.